[Credit: Documentary Film Yangyang] Tucked quietly into theaters, Yangyang confronts the unsettling issue of historical amnesia. It isn’t about nostalgia or being anachronistic—it investigates the customs, silences, and mental frameworks that allow history to be erased. Yangyang unfolds as an investigative, first-person documentary. Director Yang Juyoun narrates her own journey after discovering a family secret: an aunt she never knew, Yang Jiyoung. Jiyoung had died by suicide—or so the family claimed. The revelation dismantles Yang’s long-held image of a harmonious family, forcing her to ask whether that harmony existed only by erasing someone’s life. As she digs deeper, doubt creeps in: was it really suicide, or something closer to murder masked by shame and silence? The investigation grows tenser as the film evolves from quiet introspection to sharp accusation.

[Credit: Documentary Film Yangyang] The 78-minute work is split in two. The first half pierces the family’s carefully maintained silence—an unspoken pact of concealment. The second reconstructs Jiyoung’s story through testimonies from friends, revealing a controlling boyfriend whose obsessive behavior blurred into violence. Jiyoung’s death by poisoning at his home was hastily dismissed by both family and society as the result of “meeting the wrong man.” The family’s refusal to confront the truth—fearing dishonor over their daughter dying in a man’s house—mirrors a wider pattern of victim-blaming. Yang ultimately frames her aunt’s death as a societal murder—an outcome of the patriarchal structures that normalize silence and bury accountability. Beneath the surface of one family’s tragedy, Yangyang exposes the enduring machinery of gendered violence and erasure in Korean society.

[Credit: Documentary Film Yangyang] Yang reaches a breakthrough at the film’s end. She challenges the old belief that children who die before their parents should not have their names inscribed on family gravestones. Though the act itself isn’t shown, she persuades her father to inter her aunt’s remains in the family grave and engrave both Yang Jiyoung’s and her own names. The gesture becomes a small yet powerful victory for gender recognition in Korean society, revealing the layered meaning behind the title Yangyang.

[Credit: Documentary Film Yangyang] Contrary to first impressions, the film isn’t about Yangyang County. It’s the story of rediscovering a forgotten woman’s identity and the connection between two women sharing the Yang surname. Through their intertwined histories, the film traces the slow evolution of Korean society and the gradual formation of women’s agency. A quiet but piercing moment comes when Yang re-interviews her mother, Choi Hye-seon. When Yang asks what she would think if her daughter were found dead at a man’s house, her mother falls silent. Yang’s use of multiple camera angles captures the unspoken tension of that silence—suggesting that feminism may sometimes emerge not from loud protest, but from the empathy and understanding born in stillness.

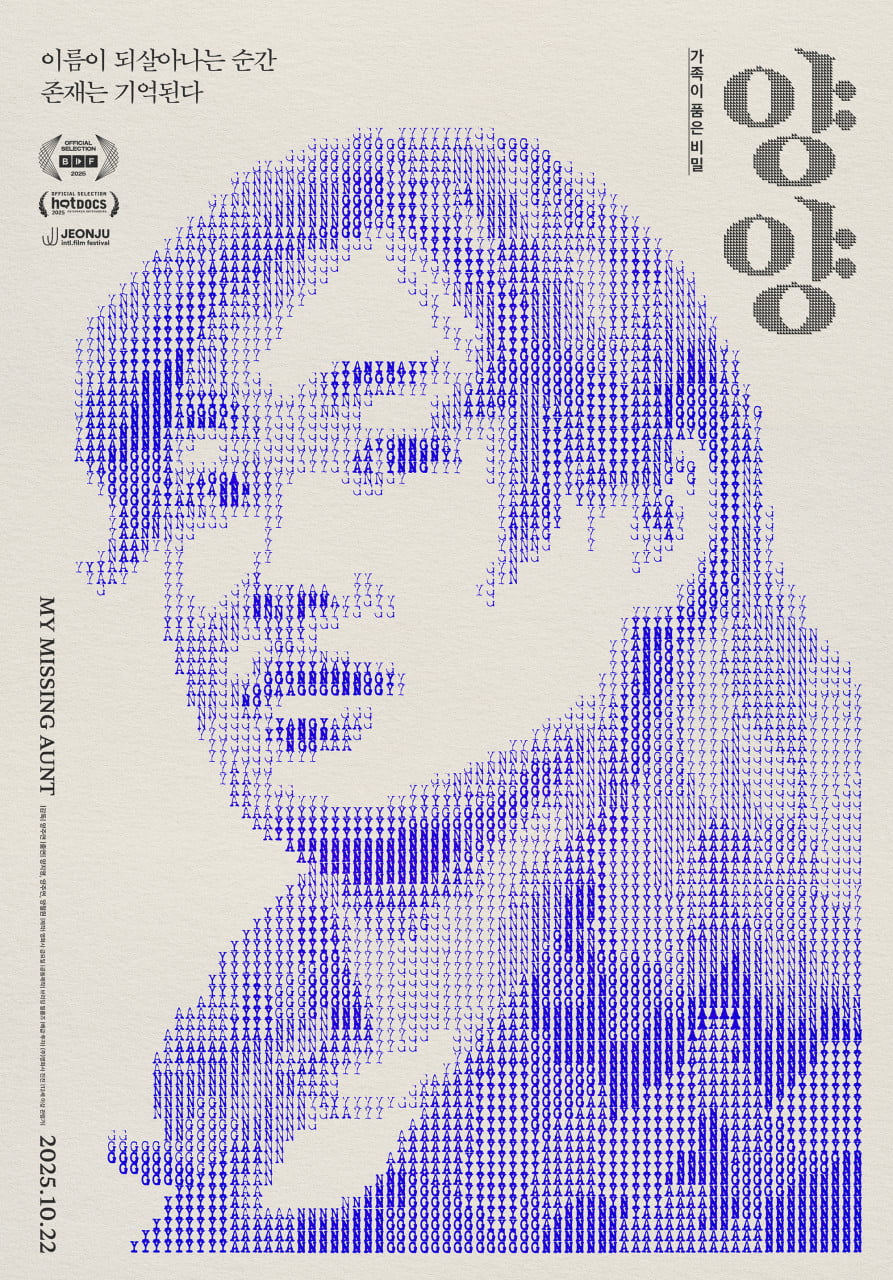

[Credit: Documentary Film Yangyang] The film’s poster visually completes its message. The letters Y.A.N.G. are arranged to form the face of Yang Jiyoung, symbolizing how patience and empathy can piece together erased memories and restore lost identities. Beneath it, the tagline—The moment a name is revived, existence is remembered—distills the entire documentary’s purpose into one line: remembrance as resistance, and naming as an act of healing. Despite its potentially academic subject matter, Yangyang rises above expectation through refined cinematography and editing. The pacing lingers deliberately, allowing silence to speak, while each frame’s composition reflects rigorous artistic control. Director Yang Juyoun and producer Go Duhyeon, both graduates of the Korea National University of Arts, demonstrate a precise mastery of lighting, contrast, and sound that elevates the film from intimate inquiry to visual poetry.

[Credit: Documentary Film Yangyang] Though its theatrical run remains limited to art house theaters, Yangyang’s influence extends far beyond audience numbers. Simply being aware of the film—and its excavation of women’s stories—broadens the conversation around feminism in Korea. The documentary embodies a quieter, more introspective form of feminist resistance. Yang’s admission that she often felt smaller after returning home from protests captures this duality: that empowerment and exhaustion can coexist. The film closes with Yang receiving another symbolic gift, a gesture of renewal, suggesting that her aunt’s restored name—and the empathy it awakened—will continue to grow with her.